Every now and then, a piece of pop culture reflects the current moment so thoroughly that its “of the moment” quality is not just an asset, but it helps the piece become an artifact that wholly conveys the attitude of its time.

One of the first video games to do that for the Trump era is “Life Is Strange 2.” Our 45th president is not a character in this branch-narrative game from Dontnod Studios, but his shadow lingers over the game like a Pacific Northwest pine tree.

“Life Is Strange 2” is the next installment in Dontnod’s “Twilight Zone”-esque universe, but it’s not a direct sequel to the 2015 original, where you play as a teen girl named Max who learns she can rewind and alter time.

By choosing different dialogue and choice options, you navigate Max through her prep school world laden with bullies, drugs, evil schoolteachers and incompetent adults. The game tackled hard themes like suicide, sexual assault, euthanasia, child abuse, underage narcotic abuse and more. By the end of the game, your choices have created so much of a Butterly Effect that they fold back on themselves, eventually leaving you with the ultimate choice: Save the world, or save your friend.

I was a big fan of the original, which made me feel true empathy for a video game character for the first time in a long time (and also used pop music to such great effects that I nearly cried in the finale). Its “Twin Peaks”-meets-“Heathers” vibe combined with some actual hard-hitting story elements is a tough balancing act, but it largely succeeded (Most of the teenage dialogue was hackneyed; I could live without ever hearing video game characters unironically use the word “hella” again).

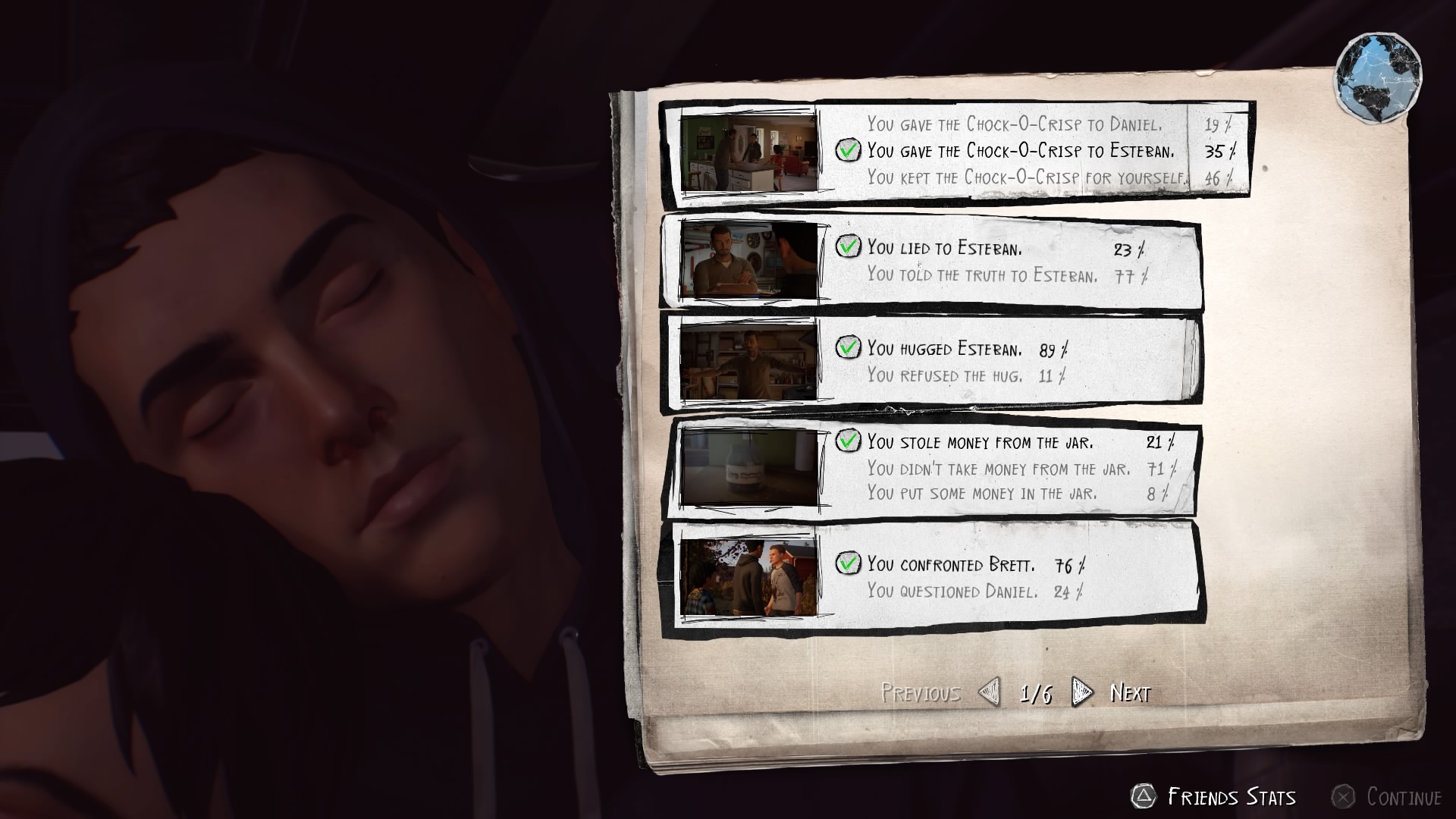

Now, with “Life Is Strange 2,” the game is the same, but different. There’s still a supernatural element (more on that later). But this time around, you control Sean Diaz, a typical teen who just wants to go out with his friends instead of dealing with his younger brother Daniel and single dad Esteban.

He skates, he drinks, he runs track, he’s nurturing a growing interest in drawing, he smokes weed, he’s trying to figure out how to get the hot girl in his class to pay attention to him. He’s also worried about what his small, conservative town thinks about his Mexican-American family in Oct. 2016, when the game is set. Multiple characters make reference to “building that wall” and “going back to where you came from.”

The inciting incident comes early in the game’s first chapter (like the first title this is an episodic game that will be stretched out over five episodes; this review focuses on Episode 1, “Roads”; the second, “Rules,” dropped earlier this year) when Esteban gets killed by a cop on his own front lawn after Daniel unleashes an unexplainable supernatural force that only shows itself when he’s afraid.

From there, Sean takes Daniel into the woods to hide out and run from the cops, protecting his younger brother at all costs. Whether they’re scrounging for food, building shelter or just goofing off, the two brothers are never separated. And it’s your goal as Sean to make sure it stays that way — the branch choices you make in this game are based on teachable moments for Daniel, not opportunities to right past mistakes, as in the first game. Every choice revolves around its ramifications for keeping Daniel safe.

The original “Life Is Strange” made me empathize with a teenage girl, despite that fact that I am not, nor have I ever been, a teenage girl. It forced me to look at situations through a different perspective, wondering which choices I would make if I were a girl.

This game didn’t need to stretch too far to make me empathize with Sean and Daniel. I’m 27 but my teenage years feel like they were yesterday, and I have a younger brother. It wasn’t hard for me to constantly ask myself, “If were in this position at 17, how would I have reacted?”

But that’s not all that impacted my decisions. Whereas my playthrough of the first game was filtered through my gender, the biggest factor with the sequel was my race. I’ve been an American white dude for a little bit longer than I’ve been an older brother, and that part of my experience colored my decision-making more than I was prepared for.

For instance, at one point while you’re on the run, you have the option of making Daniel beg for food, stealing from a racist convenience store clerk or paying for only the food you can afford. I chose to steal, satisfying the part of my lizard brain that told me I could get away with it if it were me doing it, and I would only ever steal in a time of great distress, and also it would be nice to stick it to the racist lady who was suspiciously eyeing me and my brother.

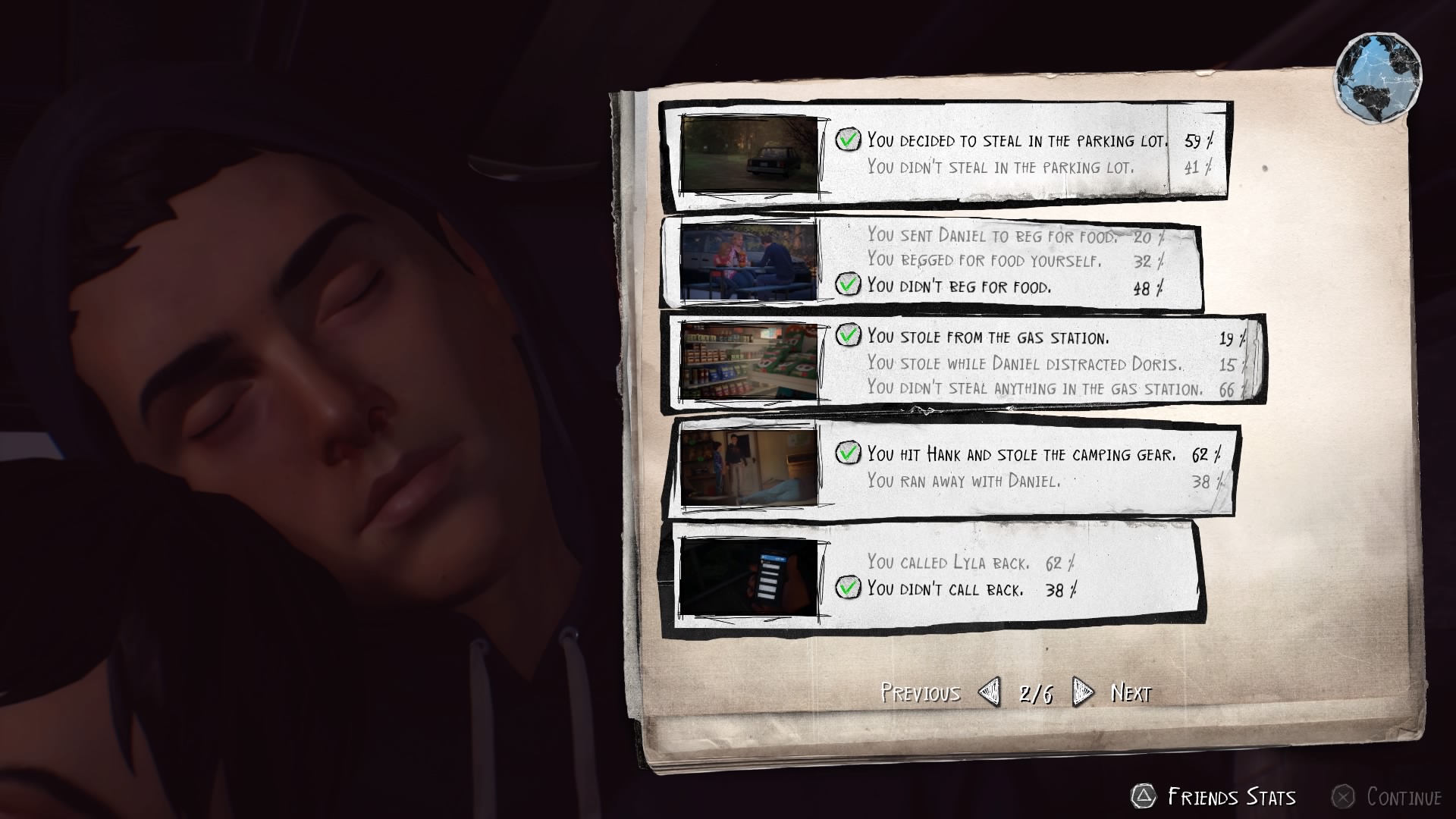

As it turns out, I was in the minority in this decision, according to PlayStation statistics from users when I finished the first chapter last month.

However, my later choice to steal a tent and some camping gear in retaliation for the racist clerk’s racist husband’s abuse and imprisonment of me while he called ICE was in the majority of user choices. Lizard brain over everything, I guess.

But whatever my reasoning for making my decisions was, the game tricks the user into thinking they have free will on what to do, when in reality, there are only a limited number of actions to take.

Users may think they have free will, but this game was coded by humans, after all. The decisions users can make in “Life Is Strange 2” have already been predetermined by the game’s creators. A player’s only choice is among the limited amount of options in front of them.

(This same subject was also tackled with gleeful abandon by Black Mirror’s standalone “Bandersnatch” episode released in late December where viewers control the main character through a series of binary choices — until the main character learns he is being controlled.)

(To a lesser extent, this same subject was also tackled with much less understanding about how algorithms or games work in the February movie “Serenity,” which must be seen to be believed.)

Going further down the rabbit hole, the fact that I, a white man, am playing a game where I am controlling a character who is Mexican-American, in a game that has gone out of its way to make a non-white protagonist, caused me to think more about the perpetual use and control of minorities by white people for personal gain. I don’t know if that was Dontnod’s intention, but it certainly got me thinking about ways that my white privilege affects minorities.

Related: ‘L.A. NOIRE’ gives the illusion of free will

I don’t think it’s too far of a reach to think that level of introspection on my part is by design. This game’s primary goal is to tell a road story about two brothers, but I think its second goal is to teach people empathy in a time when many in our country lack that trait. And getting that point across by making the protagonist Mexican-American may seem radical or “political,” but that’s the point, too.

That subtext is literally spoken into text by one of the game’s secondary characters, Brody. He’s a mobile journalist/social activist blogger who is leeching off of the gas station WiFi writing about sex workers when we meet him. He picks up the Brothers Diaz after the aforementioned conflict with the racist store owners and extends them the first moment of kindness they have experienced since their dad died.

“Everything is political,” Brody tells the brothers when explaining his work. It’s an unsubtle nod from the game’s creator’s that says they know what you may be thinking, and they don’t care. All art is political, in some way or another.

Which brings us to Donald Trump. As far as I can recall, his name is not spoken once in the whole first episode of “Life Is Strange 2.” But make no mistake, the values he and many of his followers espouse are the villains of this story.

Other games released in the last few years haven’t been afraid to get “political” (“Wolfenstein II” was apparently controversial for its stance that Nazis are…bad, and “Far Cry 5” openly courted controversy for its redneck cult shoot-em-up aesthetic, to mixed results), but “Life Is Strange 2” is the first video game to directly comment on the Tump era.

Its setting a month before the Nov. 2016 election is no accident. Neither are the references to the border wall or ICE. It would be easy to make our 45th president himself the villain here, but what the “Life Is Strange” franchise understands is that villains come and go, but ideas never die. The villains of the first “Life Is Strange” were depression, apathy, trauma, guilt and misogyny. Here, those villains are racism, fear, bigotry and privilege.

Stories like what play out in the first chapter of this game are happening right now all across America. A Florida man recently said Trump would “handle” his Iraqi neighbors as he was arrested for trying to cause damage to their property. FBI data shows that hate crimes in America rose the day after trump was elected, and a record number of hate crimes were recorded against Jews, Muslims and LGBT people in 2016. This type of hate has always been in this country, and unless we learn to empathize with others and actively fight for the rights of people who have been historically disenfranchised, it will always be here.

Art can help fight for those rights, whether it’s a song, a film, a painting or even a video game. In that way, “Life Is Strange 2” is protest art for the Trump era.

That “Life Is Strange 2” is taking on our current climate at all is commendable. That it does it so well, and with such empathy, is remarkable.

Episodes 1 and 2 of “Life Is Strange 2” are available now to play on PC (Steam), PlayStation 4 and Xbox One, with Episodes 3-5 coming soon. I’ll continue to blog my experiences with the game here.